Interconnected solutions strengthen cities

Our cities are complex systems where the built and natural environments are deeply interconnected.

As climate change drives rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and increasing water scarcity, our public infrastructure must adapt in response.

Effective solutions will depend on understanding and leveraging such interdependencies. Adapting to a changing future is designing with, not against, the surrounding ecological environment.

The City of Melbourne has embraced this thinking through innovative design of Lincoln Square - north of the city’s CBD. The development of Australia’s first multifunctional water tank has improved Melbourne’s response to its three most impactful climate hazards: flooding, water stress, and urban heat.

Within Melbourne’s short history water management has played a large role in the city’s development.

The ghost of Williams Creek

Melbourne’s colonial settlement began in 1835 with the landing of the Enterprize on the northern bank of the Birrarung. Two years later surveyor Robert Hoddle laid out the Hoddle Grid that would give rise to the straight, wide roads and laneways that culturally define the heart of Victoria’s capital.

The grid, however, was impose with little regard for the natural landscape or climate. In an effort to replicate the urban form of European cities, the swampy banks and surround marshlands that were flood-prone were built upon.

Elizabeth Street was built along a natural depression in the land known as Williams Creek. The creek would not always flow, but the shallow valley would accumulate rainfall and carry it to the Birrarung.

In the first ten years Melbourne flooded six times.

In attempts to minimise the flooding, wetlands and waterways were buried under layer upon layer to transform swamps and marshland into firm, stable ground. Streets that were once waterways, wetlands, and swampy riverbanks frequently flooded Melbourne’s streets.

Without natural runoff for water the flooding would become more severe. Elizabeth Street and Flinders St Station would flood several times throughout its short history.

Melbourne in 1838, from the Yarra Yarra. Colour lithograph by Clarence Woodhouse. You can see Elizabeth Street in the dip on the right, with footbridges leading across it at intervals (State Library of Victoria).

One of the most recent and notable examples is in 1972 when Melbourne experienced 75mm of rain in 17 minutes. Elizbeth St became William Creek again. A wall of water travelling 12 knots barreled south-bound into the CBD.

Emergency roadside assist received 1200 calls for help as people, trapped in their cars, became submerged in the floodwaters. Public transport shut down temporarily. The fire brigade answered 45 calls of electrical equipment short-circuiting from the flood waters. Shopkeepers lost thousands of dollars worth of stock.

In 1972, 75mm of rainfall flooded Melbourne’s Elizabeth St. Reproduced courtesy The Age. Photo taken by Neville Bowler.

Lincoln Square water sensitive urban design

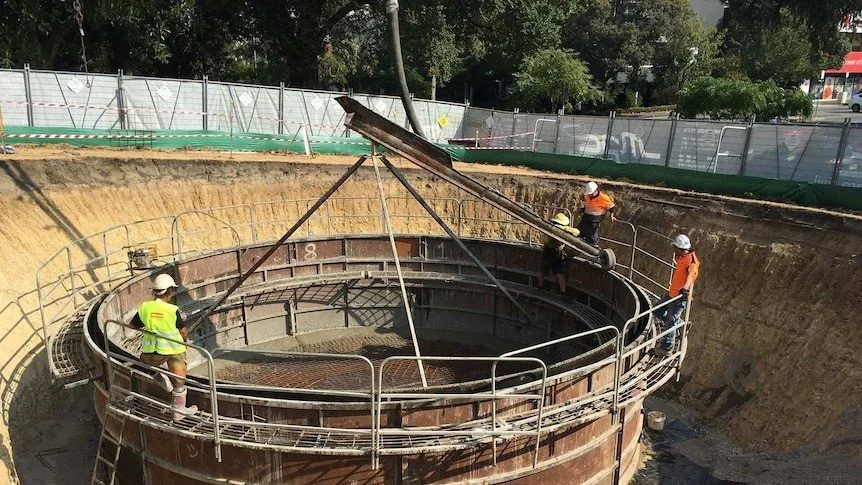

As floods continued to submerge Melbourne’s street, the City of Melbourne invested in what is Australia's first multifunctional smart tank underneath Lincoln Square.

Commissioned in 2016, the $3m joint venture with the Victorian Government, combines advanced water management technology with landscape design to deliver climate resilience benefits.

During the year as it rains the tank collects water – saving thousands of litres of drinkable water, annually. This water is used to keep the surrounding green spaces lush and green during summer months when green spaces are needed the most to cool down urban areas.

What sets this project a part is the use of smart technology to operate. The system is equipped with sensors and automated controls that monitor rainfall forecasts, and tank levels in real time. Therefore, when large downpours are anticipated the tank can be slowly discharged beforehand to then collect the heavy swell, reducing the amount of water that pools around Elizabeth and Flinders St Station.

“We manage 480 hectares of parkland across the city, so it’s important that we use water wisely to protect our iconic gardens from drought and extreme weather conditions”

The dual functionality tackles Melbourne’s major climate risks: flooding, water stress, and heat stress.

It reduces the risk of localised urban flooding by capturing stormwater before it can overwhelm the drainage system. It combats urban heat by supporting vegetation and tree canopy that provide shade and cooling through evapotranspiration. It also addresses water stress by offering a sustainable source of irrigation during dry periods, which helps protect biodiversity and maintain green space quality.

This project is unique not only for its multifunctional approach but also for its seamless integration into a public park. Unlike traditional water infrastructure, the tank is hidden beneath the landscape, allowing the park to remain fully accessible and visually appealing. By embedding climate adaptation infrastructure into the fabric of public space, Lincoln Square’s smart tank sets a new benchmark for how cities can respond to climate risks in a way that is both technically effective and community-focused.

Connected to the climate

Climate adaptation is most effective when it embraces the interconnected nature of urban systems. A single solution, when thoughtfully designed, can address multiple climate risks at once. Projects that begin by targeting one climate impact can be enhanced to form integrated systems that mitigate a triple threat of urban heat, flooding, and water stress.

By understanding the land and its ecosystems, we gain insight into how human settlements can exist in harmony with their environment. Melbourne shows that combining water storage, diversion, shading, and natural absorption doesn’t just respond to climate hazards, it creates more resilient, livable cities through integration, not isolation.

Further Reading

From the Archives, 1972: Chaos as floods batter Melbourne

Melbourne CBD Local Flood Guide

Melbourne's Hidden Waterways: Revealing Williams Creek

Learn more about how smart infrastructure can reduce climate risk of our cities by reaching out.